What can I patent in my software startup? Can you actually patent software? Welcome to episode II of my patent 101 trilogy. Episode I was all about why to file a patent, or not. Now it’s time for a deep dive into what has historically been accepted and rejected. Plus best practices, specifically if you’re into filing funky blockchain patents. Not only because that keeps me entertained lately, but blockchain also serves as a great example for today’s view on software patents.

Disclaimer: This is a view on patents from an entrepreneur’s perspective. Even though I co-authored a dozen world-wide patents in various companies, I am not an IP lawyer.

The European Patent Office (EPO) defines extensive guidelines for eligibility, and is generally very restrictive on software patents. As a consequence, I focus on the US in this post. Patent eligibility in the US is defined under the Patent Act 35, US Code paragraph 101. With reference to a gazillion court rulings, some of which I’ll discuss below.

You patent a technical innovation. That’s understood to mean a product or operating procedure in any technological field. There’s a bunch of material conditions that come with that.

Let’s go over these one by one.

Patent lawyers always refer to the person of (ordinary) skill in the art (POSITA) for a certain domain. They actually have many of these professionals locked up in a closet in their office and pop them out whenever required. One for each domain. This fictional creature is used in two cases:

What’s more: this fictional person’s knowledge and abilities are specific to the point in time an application was filed. By the time, years later, a matter is argued with the patent office (PTO) or in court, the person of ordinary skill-in-the-art will travel back in time! To provide a perspective of the technological landscape at that moment.

A boundary case regarding novelty is an invention that copies an idea from one domain to a rather unexpected new domain. A person skilled-in-the-art in each domain would not have come up with the idea to apply the invention in the other domain. Hence the cross-over to a non-related domain may be deemed as novel.

European patent law follows a concept referred to as a further technical effect. An invention needs a technical effect to be valid. A technical effect of software can be a reduced memory access time or better control of a robot arm. Visualizations, for example, do not have a direct technical effect. They only show stuff and leave it up to a human to trigger a technical effect based on what they see. As there is no guaranteed action from the visualization, the effect is deemed as invalid. The human operator could still do the wrong thing—and they tend to do that all the time.

A known example is a dial in a medical device to control temperature. If the temperature is set to above a preset value, the dial physically needs more pressure to turn. Hence protecting the doctor from setting a too high temperature, which could cause harm to the patient. The direct physical feedback makes it harder for the doctor to set a dangerous temperature. Now that is deemed as a valid technical effect. The doctor just looking at a temperature readout is not.

The UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) is known to grant patents to inventions that are partly or wholly implemented in software. In 2008, the Symbian won the right to patent a DLL interoperability trick that makes other software run more quickly. Specifically, the UK Court of Appeal stated that because a computer with Symbian’s software operated better than a similar prior art computer, it was patent eligible. A technical effect.

There must be a technical relationship among the claimed inventions. The claims build on one another or involve the same corresponding “special technical features”. With the special feature making a contribution over the prior art.

When there is no such special technical feature common to all claimed inventions, there is no unity of the invention. In that negative case, each (group of) claims needs to prove their individual contribution over prior art. Usually that means your application will be rejected. My dad’s claim to fame is that among all solar physicists that play the flute, he no-doubt is the best white-water kayaker. Patent examiners won’t fall for that one.

Alice Corporation owned four patents on financial-trading software to reduce “settlement risk”: the risk that one party will pay up while the other doesn’t. Alice accused CLS Bank of infringement. CLS Bank consequently filed suit against Alice on the basis that the patent claims were invalid. And won.

Despite a clear-cut judgement, district court judges found the claims to be patent-ineligible abstract ideas. Turning an abstract concept method into software on a computer does not make it patent-eligible subject matter, so they reasoned. Alice took a fundamental economic practice (of hedging risk) and implemented it in software as is. As hedging risk is an abstract idea, the claims were deemed abstract too.

Since the 2014 Alice decision, software patents in the US have suffered a pretty high mortality rate. Despite the court not mentioning software anywhere in the opinion! Federal Circuit Judge William Curtis Bryson explains:

“In short, such patents, although frequently dressed up in the argot of invention, simply describe a problem, announce purely functional steps that purport to solve the problem, and recite standard computer operations to perform some of those steps. The principal flaw in these patents is that they do not contain an ‘inventive concept’ that solves practical problems and ensures that the patent is directed to something ‘significantly more than’ the ineligible abstract idea itself.”

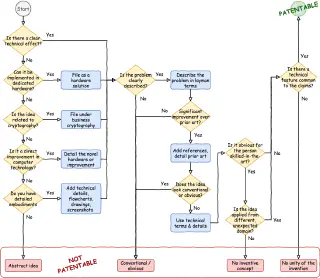

Alice extends the 2012 ruling of Mayo v. Prometheus, where the Supreme Court ruled that a medical patent was claiming a law of nature itself and adding nothing truly inventive. From this emerged a two-part test for patentability.

The Mayo/Alice test:

- does the invention go beyond an abstract idea, and

- is there an inventive concept beyond the obvious?

Predating Mayo and Alice, the 2010 Federal Circuit (the highest patent court below the Supreme Court) decided in Bilski v. Kappos. The court enforced patent applications to satisfy the so-called machine-or-transformation (MOT) test. This requires software to be described as being tethered to a certain machine embodiment. As a logical knee-jerk reaction, most of today’s software patents bake the software into the hardware in some artificial way.

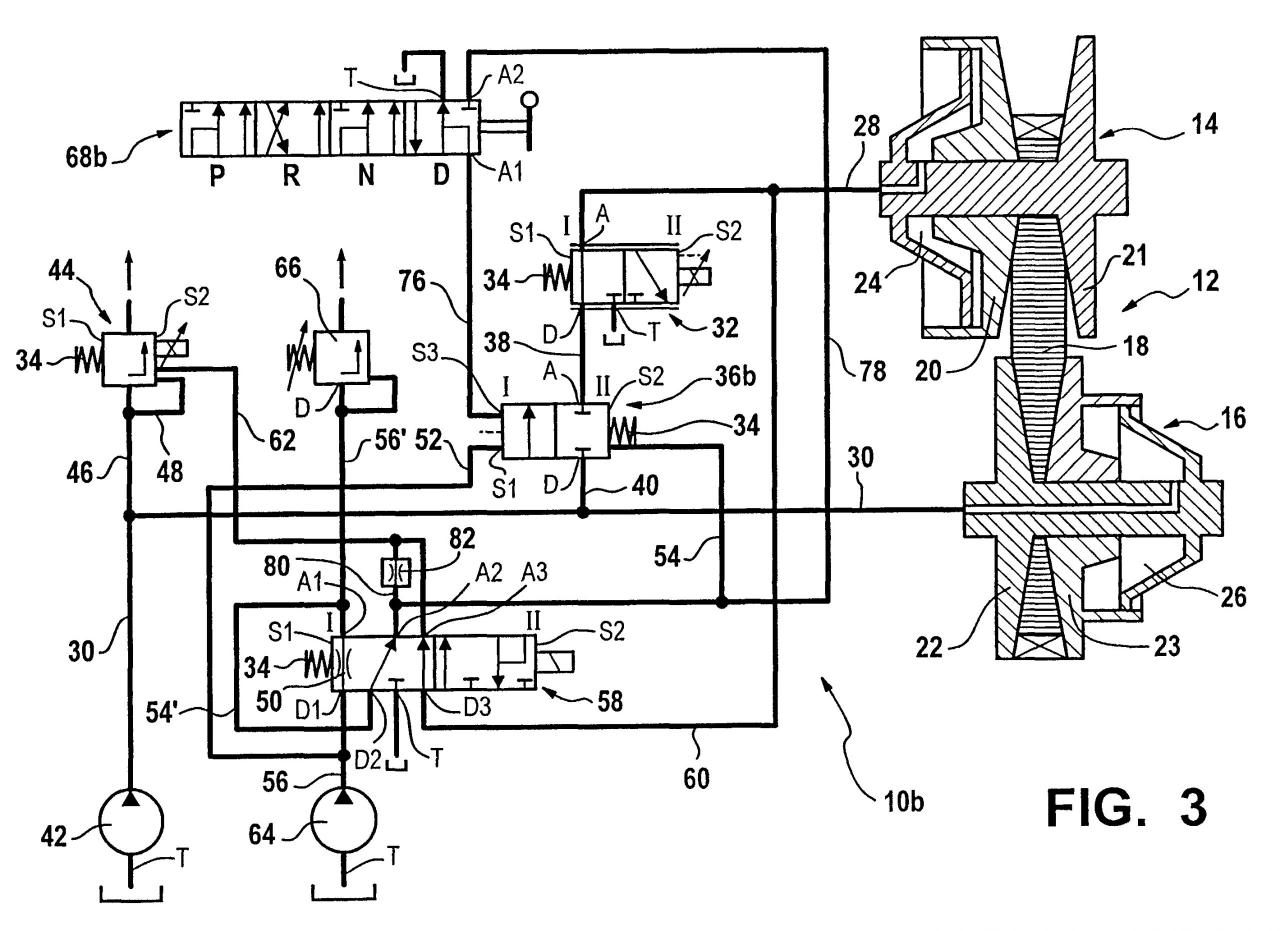

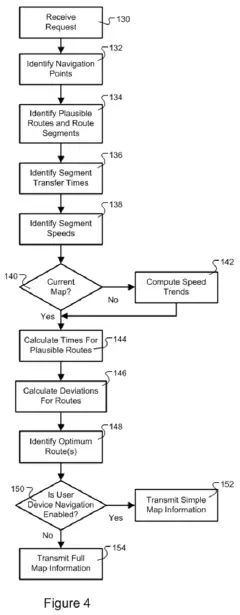

Blockchain patents typically list separate claims on a hardware system with processors running the blockchain to ensure such a link with the physical world. A beautiful example is this blockchain interoperability patent from Accenture’s masters in the art of obfuscation. The patent talks about circuitry everywhere, but then goes on to explain this could also be run as Docker containers on a virtual machine. Wait, Docker containers? In the claims it describes:

So it’s just software after all! Dressed up as sophisticated hardware.

Alas, that’s what you get when US courts form an opinion on technology. At least the MOT test has been applied somewhat consistently. It is still today pretty wild what a patent examiner can get away with simply by deeming your claim as “abstract”.

Dumbing down the technical disclosure so even a Justice of the Supreme Court can understand it, is a mistake.

As a result, for a software patent to be eligible, it typically needs complex flowcharts and overly detailed implementations and tortured descriptions. Feast your eyes on this flowchart nirvana. This Microsoft blockchain patent even goes so far as to include a block diagram of a mobile phone to add totally irrelevant detail on where the invention could be applied. Generally write your invention such that only a domain expert doing advanced mental gymnastics can grog it.

The 2016 Enfish vs. Microsoft case somewhat restored the legitimacy of software patents. The case built on the technical effect doctrine followed by the European Patent Office. An “improvement in computer capabilities’ “ was deemed patent eligible. Even though the underlying computer received no improvement in its physical operation.

In a subsequent Audio MPEG vs. HP, the court looked at claims on MPEG audio coding. Citing Enfish, the court found that the claims were not directed to an abstract idea as the invention solved a computer-specific problem: it enabled more efficient data storage than would be possible without compression.

Wohoo. So software is not always abstract ideas only, as long as it brings computer technology itself a step further.

Since these cases, the US courts have been pretty confused as to what marks an abstract idea (Alice) versus an improvement in computer technology (Enfish). One court may find a software patent not patentable, but another court may find a similar software improvement patentable. As Paul Michel, former Chief Judge of the Federal Circuit, testified, the application of Alice has been “excessively incoherent, inconsistent and chaotic.”

So what do all these US cases mean for writing my patent application? A summary:

There are more recent cases, such as Berkheimer that helped to assess what is conventional or not. Many of these had an effect in the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance to help US patent examiners in decision making. Still, the jury is not fully out on software patent eligibility rules or how to apply them. And I didn’t dive even into the peculiarities and cases on software patents from the UK, Canada, or Europe…

What is your experience with filing software patents?

Big thanks to IP attorney Otto Steinbusch for his invaluable review comments! In Episode III of my startup patent trilogy, we dive into the anatomy and language of a patent. Legalese 101 for programmers. Stay tuned.

About Martijn Rutten

Fractional CTO & technology entrepreneur with a long history in challenging software projects. CTO at LUMO Labs impact VC. Former CTO of scale-up Insify, changing the insurance space for SMEs. Former CTO of fintech scale-up Othera, deep in the world of securitized digital assets. Coached many tech startups and corporate innovation teams at HighTechXL. Co-founded Vector Fabrics on parallelization of embedded software. PhD in hardware/software co-design at Philips Research & NXP Semiconductors. More about me.

Related Posts